Guest Post: The Top 7 Whiskies of the Gilded Age

By Julie Montagu, Countess of Sandwich and a Gilded Age historian

We have a treat this week! Over the past year, I’ve been working closely on multiple projects with Julie Montagu, MA. She’s a Gilded Age historian, speaker, presenter, and the 12th Countess of Sandwich.

This week, we’ve decided to swap articles. I posted over on her Substack (Gilded Heiresses) about how Scotch became the drink of Gilded Age America, and she wrote this incredible article about the top whiskies of the Gilded Age.

We hope that you enjoy!

Xx Shelly

The Top 7 Whiskies of the Gilded Age

Whisky and the Gilded Age may seem like an obvious pairing now (think crystal tumblers, smoky drawing rooms, and splashes of amber in cut glass), but in the early 19th century, few would have envisioned Scotch whisky, in particular, becoming the drink of dukes, debutantes, and Fifth Avenue dynasts.

Once the fiery, rustic spirit better suited to Highland crofters than high society, whisky became a global marker of refinement by the end of the century. But how did this happen? And which whiskies defined the era?

Pull up a chair, pour yourself a nip, and let’s dive in.

Setting the Scene: From ‘Poor Man’s Dram’ to High Society

Our story begins with transformation.

Until the mid-19th century, Scotch whisky was notoriously rough: intensely peated, wildly variable in taste, and usually distilled in small, local batches. It was dubbed ‘the poor man’s strong drink’.

The turning point came with the Excise Act of 1860, which legalised the blending of malt and grain whisky and allowed distillers to create a smoother, more approachable spirit that could be scaled up for wider appeal.

The revelation was in the blending, which took the fiery rawness of malt and softened it with lighter grain whisky, making Scotch palatable to those who might once have turned up their noses.

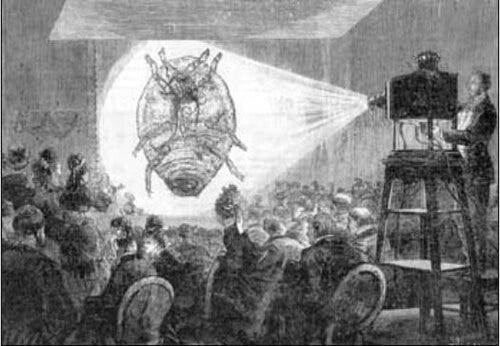

Then came the crisis from across the channel, which catapulted the Scots’ liquid nectar into stratospheric heights of popularity: the great French wine blight. In the 1870s and 1880s, the phylloxera insect ravaged French vineyards, devastating supplies of wine and brandy. With cognac suddenly scarce, British and American elites cast around for ready alternatives.

Enter: Scotch whisky, newly smoothed by blending, and ready to step into the breach.

Meanwhile, in America, bourbon and, rye had long histories of their own. Kentucky bourbon—rich with corn sweetness—and Pennsylvania rye—spicy and bold—were staples in taverns and saloons.

By the Gilded Age, these whiskies were being bottled and marketed more consistently, appearing in the cocktails that became fashionable in metropolitan hubs like New York and Chicago. But little did they know that the Scottish underdog was hot on their tail, and soon ready to take the States by storm…

Against this backdrop, whisky moved from humble origins to global luxury. Here are the seven that defined the Gilded Age.

Cardhu: A Woman’s Touch

Cardhu began as a modest Speyside distillery in 1824, but its fate changed under Elizabeth Cumming in the 1870s. Widowed young, she expanded the distillery with a new stillhouse in 1885, increasing capacity and cementing Cardhu’s place in the blending revolution. And most remarkably, she did so in an industry dominated by men.

Cardhu’s spirit was prized for its light, honeyed character, with fruity notes and gentle smoke (softer than typical Speyside malts at the time), which made it a favourite among blenders. The famous Johnnie Walker distillery, in particular, relied on Cardhu’s elegance as a cornerstone of its blends.

Though not yet bottled as a single malt for elite tables, Cardhu was present in glasses of blended Scotch poured everywhere from Mayfair clubs to New York hotels. It was the invisible hand behind whisky’s new reputation for smooth sophistication.

The Chivas Brothers: Luxury by the Bottle

In 1801, at 26 and 22 years old, the Chivas Brothers, James and John, left their poor, rustic upbringing behind and headed to Aberdeen to launch their careers as luxury grocers supplying fine goods to the Victoria elite.

By the 1840s, they were creating proprietary blends of aged whisky in response to their affluent clients’ demand for better Scotch. Their reputation went from strength to strength, and by 1843, they were appointed purveyors to Queen Victoria at Balmoral.

Chivas whiskies were richer and more refined than most, favouring smoothness over smoke, with mellow fruit and a velvety finish. This style appealed to aristocrats who wanted something polished to match their claret and Champagne.

Though the famous ‘Chivas Regal’ label would not debut until 1909, the groundwork was laid in the Gilded Age, when a bottle from Chivas signalled both wealth and discernment. It was whisky for the drawing room, not the tavern.

Johnnie Walker: The Striding Scotsman

Even those without the faintest interest in whisky are likely to recognise the iconic Striding Man, the emblem of Johnnie Walker.

The Walkers’ ascent, however, began much earlier, in 1820, when John Walker opened a grocer’s shop in Kilmarnock and began selling his own blends of whisky. At the time, most Scotch was fiery and inconsistent, but John’s careful blending quickly earned him a reputation for reliability. His son, Alexander, then expanded the business after John’s death in 1857, laying the foundations of a true blending empire.

By the 1860s and 1870s, the company was innovating not just in taste but in presentation. The introduction of the square bottle meant fewer breakages at sea and allowed more bottles to be shipped at once, while angled labels made the brand instantly recognisable.

This combination of consistency, clever branding, and global distribution proved irresistible in the Gilded Age. By the 1880s, Johnnie Walker was being exported across the empire and into the lucrative American market. Modern, cosmopolitan, and dependable, the brand could soon be found in the hands of elites everywhere, from London clubs to New York brownstones.

Dewar’s: Whisky Goes Global

Few brands embraced the theatrical spirit of the Gilded Age quite like Dewar’s.

Founded in 1846 in Perth by John Dewar, it was his flamboyant son Tommy Dewar who made it a household name. Between 1892 and 1894, he embarked on a two-year world tour, promoting the brand in 26 countries and writing a book about his travels.

The unorthodox publicity stunt worked, however, quickly putting Dewar’s on the map as one of the premier Scotch whiskies available. But it didn’t stop there. In 1898, Dewar’s produced It’s Scotch!, one of the world’s first film advertisements, screened in New York.

The message was clear: Dewar’s was not just a whisky but a modern global brand.

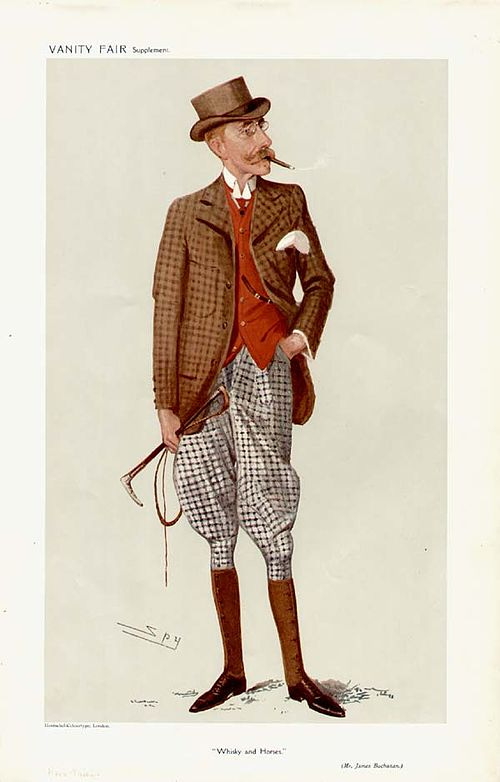

Buchanan’s: The Whisky of Prestige

When James Buchanan founded his whisky company in London in 1884, he was a man with a vision. Born in Canada to Scottish parents and raised in Glasgow, Buchanan worked as an agent in the whisky trade before striking out on his own. After moving to London and witnessing an untapped market in England for bottled Scotch, he set about making his own, and so Buchanan’s blend was born.

Buchanan’s first big break came in 1885 when his whisky was chosen to supply the House of Commons bar, giving it a prestigious foothold in political and social circles. From there, his reputation grew quickly. He was a master of marketing as well as blending, insisting on consistent quality and distinctive branding, even travelling to South America himself to establish export markets.

By the 1890s, Buchanan’s had become a byword for refinement. His blends were deliberately understated, with clean, fruity notes and a soft finish, designed to suit palates accustomed to finer tipples rather than fiery spirits. And in 1898, his efforts were rewarded with a Royal Warrant from Queen Victoria, followed by further warrants from Edward VII and George V.

Old Forester: Bourbon in a Bottle

In America, whisky’s Gilded Age story was shaped by the First Bottled Bourbon™, Old Forester, founded in Louisville in 1870 by George Garvin Brown. It was the first bourbon sold exclusively in sealed glass bottles, at a time when most whisky was still sold in barrels and prone to adulteration.

To guarantee its consistency, Brown batched his bourbon from three separate distilleries, sealed it in exclusively glass bottles and signed each one as a personal guarantee of quality. The flavour was classic Kentucky bourbon: caramel, vanilla, and baking spice, with a warming, full-bodied profile. Safe, consistent, and elegantly marketed, it appealed to the growing urban middle and upper classes, who valued trust and good branding.

For American elites, Old Forester was a symbol of modernity, as reliable in a Fifth Avenue bar as it was in a Louisville parlour.

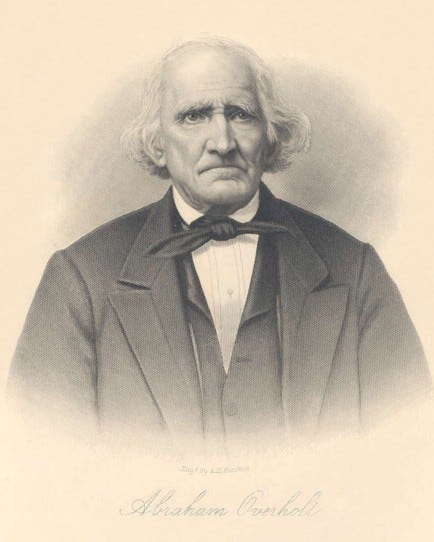

Old Overholt: America’s Rye

Old Overholt, America’s oldest continuously produced whiskey brand, originated in Pennsylvania in the early 19th century and by the Gilded Age had earned a reputation as one of the nation’s most esteemed rye whiskies.

In 1800, Henry Oberholzer, a German Mennonite farmer from a region famed for rye distilling, began producing whiskey. A decade later, his son Abraham Overholt transformed the family tradition into a thriving enterprise. Rye, spicier and drier than bourbon, had long been a staple in the northeast, but in the 1880s it found new fame as the backbone of cocktails like the Manhattan and Old Fashioned.

Old Overholt was known for its peppery bite, with hints of cinnamon and oak. Bold enough to hold its own in mixed drinks, yet smooth enough to sip neat. Renowned for its reliability and consistent quality, the brand was among the first whiskies to embrace the federal Bottle in Bond Act, a pledge to authenticity that secured its place in American bars and homes alike.

By the late 19th century, if bourbon was the taste of Kentucky, rye was the flavour of New York, and Old Overholt was its banner bearer.

From Barrel to Ballroom

By the dawn of the 20th century, whisky had cemented its role as the drink of choice for elites on both sides of the Atlantic.

Scotch blends, smooth, consistent, and luxuriously branded, dominated in Britain and abroad. Meanwhile, bourbon and rye defined America’s own drinking culture, appearing in the cocktails of New York’s gilded hotels and speakeasies-to-come.

For the Gilded Age’s high society, whisky was a statement of cosmopolitan taste, modern branding, and luxury distilled. From humble beginnings to toast of the town—it was a spirit, quite literally, of the age.

Thanks so much to Julie for a fascinating article! For more from Julie, subscribe to her publication, Gilded Heiresses, at this button:

And if you’re visiting from Julie’s world: hello! I hope you’ll stay.